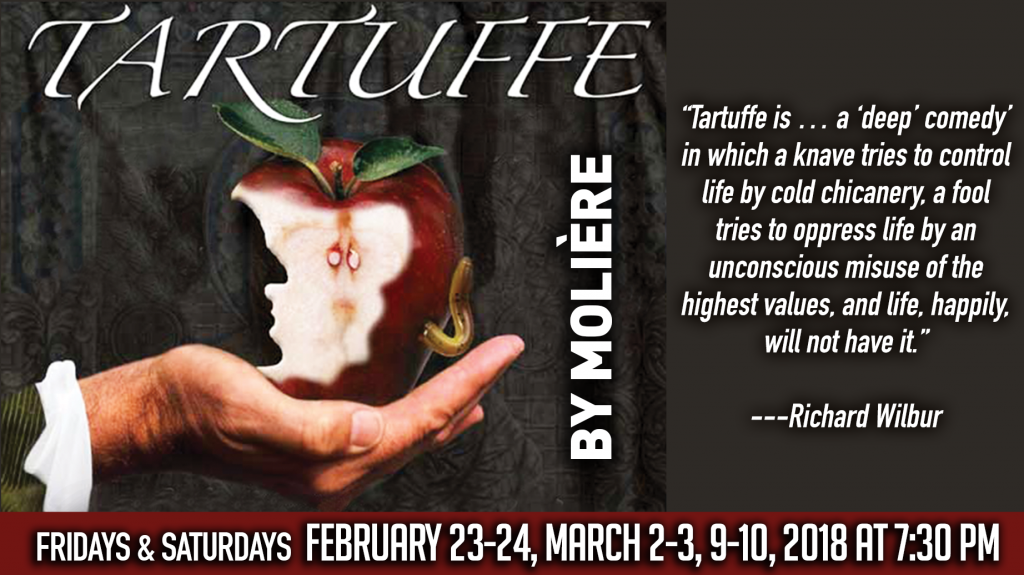

INDEPENDENT PLAYERS continues its 40th Season with Moliere’s masterpiece Tartuffe which it first presented in 1991; it opens February 23 and runs February 24, March 2-3 & 9-10. Directed by Artistic Director Don Haefliger, it stars Gabor Mark, Dana Udelhoven, Lori Rohr, Steve Connell, Sylvia Grady, David Hudson, Kelsey Richmond, Blase Horn, Brian McLeod, Jonathan Horn and James Gabl. Performances are at the Elgin Art Showcase, 164 Division St., Elgin. Curtain time is 7:30 PM. Tickets are available online and at the door (cash/check).

In order to set the stage for INDEPENDENT PLAYERS’ upcoming production of Moliere’s Tartuffe, it will present some background into the life of the playwright, the play itself, the theatre of the late 17th Century and the society of the time. The commentary will be more extensive than is most often presented, but it is hoped that the reader will find it informative and enlightening.

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (1622-1673) was born into a prosperous mercantile family with connections at court; his father, Jean Poquelin, was the upholsterer to the court which carried an annual pension. He also educated his son in the traditional disciplines of the humanities, philosophy, and the classics and must have intended a life at court for him. In 1643, Jean-Baptiste joined with the Illustre Theatre, a theatrical company run by the Bejart family, took the stage name Moliere, and after a brief period performing in Parisian tennis courts, left with the company to play in the provinces. In 1658, after several hard and impoverished years of touring, when Moliere is thought to have mastered the techniques of commedia dell’ arte, the company was invited to perform in Paris.

Moliere’s career was closely tied to the court. In 1660, he received the position of court upholsterer and the income it provided. More important, Moliere became an important playwright and both wrote and acted in a splendid series of plays that satirized the manners and morals of elegant society: Les Precieuses Ridicules (1659), Sganarelle (1660), School for Husbands (1661), School for Wives (1662), Don Juan (1665), The Misanthrope (1666), The Doctor in Spite of Himself ((1666), The Miser (1668), The Learned Ladies (1672), and The Imaginary Invalid (1673). Moliere also prepared other entertainments at court, including many royal pageants, ballets, and machine plays devised by and for Louis. In addition to being a great dramatist, Moliere was a fine comic actor as well and performed in his own plays; he died shortly after playing the title role in the fourth performance of The Imaginary Invalid.

His theatrical company was the most influential of its day. After his death, his young wife Amanda Bejart and the actress Mademoiselle Champmesle—newly defected from the rival company at the Hotel de Bourgogne—established a new company, the Comedie Francaise. Yet although Moliere achieved extraordinary status at court, because he was an actor, he remained stigmatized in ways that other known playwrights were not. Following its standard practice, and perhaps because of Tartuffe’s notoriety, the church refused to bury Moliere in sacred ground. Louis XIV intervened, but was only able to persuade the Archbishop of Paris to bury Moliere in a parish cemetery. The burial was conducted at night, by two priests, with no funeral ceremony.

The fortunes of Tartuffe suggest Moliere’s importance at court. When he first produced the first three acts of the play in 1664, the clergy protested and banned the play from production in Paris. Many of Moliere’s plays had excited controversy, and, in this case, Moliere appealed to the king and proceeded to revise the play. Louis’s attitude is perhaps revealed by the fact that he made Moliere’s company the “King’s Company” in 1665, but even the throne could not prevent the clergy from censoring Moliere’s second version of the play in 1667, newly titled The Imposter. Moliere finally produced the play to wild acclaim in 1669.

The satire follows the travails of dithering Orgon, a middle-aged fool who falls under the spell of a charlatan—Tartuffe, a duplicitous would-be man of God who is more in thrall to sex and money. Orgon’s gullibility drives his family to despair, especially when he endeavors to marry off his daughter Mariane to his new friend. Tartuffe’s boldness knows no bounds and Orgon gets royally “Tartuffed” before he finally comes to his senses.

The play satirizes the religious hypocrite and is intended as a critique of the misuse of religion. Yet through plot development and its characters, Moliere makes an even broader social commentary touching upon the Enlightenment ideals of reason and the hierarchical structure of society. This is most apparent in the way Moliere upholds the Enlightenment belief that females are capable of reason, demonstrating their capability for rationality and cleverness, and presents a critique of an irrational patriarchy which attempts to oppose them. It is the female characters in Tartuffe who recognize the hypocrite and his malice, demonstrating their clear sense of right and wrong. Their insistence on revealing what is really going on and their attempts to subvert the irrational patriarchal authority allow them to succeed where the men of the family failed in bringing about the unmasking of Tartuffe’s fraud. This happens despite the power exercised by Orgon and the social world of the time where women exist in utter subordination to fathers and husbands.

French society of Moliere’s time was one in which men exercised political and economic power and where subordination of women was accepted as necessary. The patriarchal position of power held true in the domestic household as well—as demonstrated by Orgon’s attempts to exercise authority over it. He makes this clear when he insists that Mariane will marry Tartuffe because it is a father’s privilege. This sets the stage for the conflict that plays out later and demonstrates that he cannot see through Tartuffe’s mask of hypocrisy. Because of his foolishness and failure to reason, Orgon forces his own son Damis out of the house. Later, he even hands over the deed of his household to the hypocrite. In other words, he has the authority to make poor choices which is antithetical to the enlightenment ideal of reason. His arrogance prevents him from listening to the voices of reason that try to dissuade him, which allows Moliere to show how the women of the play act with reason and cleverness by subverting his authority.

At the forefront of all of this is the maid, Dorine. She shows her understanding of human nature, which demonstrates the capacity for women to reason. Mariane’s character is that of the submissive daughter; this character type strongly demonstrates Orgon’s patriarchal dominance over the women in his household. The degree to which Dorine must resort to subversion against Orgon’s irrationality shows the extent to which the rational capabilities and will of the women in Moliere’s society are undervalued and how that patriarchal authority and arrogance are far too great.

Elmire uses Tartuffe’s inappropriate advances on her to trap him—she’ll tell Orgon nothing of what occurred if, in return, he will swear to advocate as forcefully as he can the marriage of Valere to Mariane. Elmire has Tartuffe trapped; then Damis enters and tosses accusations at Tartuffe to reveal his deceit. That this near-resolution to the conflict by a female is ruined by the overly zealous actions of a young man is a strong critique of the contemporary perception of female capabilities versus male capabilities.

The failure of the men to oppose Orgon and successfully reveal Tartuffe’s hypocrisy allows Moliere the opportunity to further demonstrate the capabilities of women. As it is they who reveal the hypocrisy of Tartuffe and not the men of the house, his unmasking is a testament to female reason and cleverness.

By convincing Orgon of Tartuffe’s hypocrisy, women, specifically Elmire, have broken down the hierarchical structure which had opposed and suppressed them. Thus the play is a major commentary on and criticism of the role and position of women in the social hierarchy of the time. Moliere shows that women can subvert the subordination which their society demanded of them. This is why Tartuffe was so controversial! Thus he upholds the Enlightenment belief that women are as capable as men of reasoning,

and then takes it even further. He demonstrates their cleverness and cunning through their acts of subversion against the patriarch’s authority. This rebellion against irrationality is vindicated when they successfully “lift his mask” and reveal his hypocrisy. This was a major reversal of the social position and perception of women in Moliere’s time.

+++Here is another very interesting commentary on TARTUFFE………………..

The Catholic church criticized Tartuffe for its portrait of hypocritical piety, but the fact that Moliere played the part of Orgon may suggest that the play is as much about Tartuffe’s effect on that benighted householder as it is about the title character. For if Tartuffe is hypocritical, Orgon is obsessed, less with piety than with his own desire to achieve a kind of total power and authority in his household, a kind of domestic absolutism; he is, in a sense, a comic, bourgeois Louis XIV in miniature. Moreover, Tartuffe dupes Orgon not by tricking him, but by inviting Orgon to fulfill his own fantasy of autonomy and authority. As he brags to the sensible Cleante, under Tartuffe’s teaching, “my soul’s been freed,/ From earthly loves, and every human tie: /My mother, children,

brother, and wife could die,/ And I’d not feel a single moment’s pain.” Helping Orgon to realize this fantasy, Tartuffe transforms him into a kind of monster: Orgon comes near to selling his daughter, disinheriting his son, allowing his wife to be raped, and losing his family’s property and fortune.

Tartuffe is very much a play of the world, a satiric comedy. Set in an urban landscape, the play insistently translates the idealized passions of tragedy and romantic comedy—love, honor, loyalty—into their ironic counterparts—lust, hypocrisy, betrayal. Moliere peoples the play with individualized versions of the unchanging types of commedia dell’ arte and the Roman comedy that inspired it: the reasonable and attractive heroes; an old, pedantic, self-absorbed dupe; a wily and conniving villain; a clever and witty servant. Yet Moliere reinvents this range of stock characters, brilliantly turning his play toward an exploration of the folly of self-deception. Tor while we might take the neoclassical conflict between reason and the passions to be the hallmark of tragedy, it surges through this play as well. Orgon’s passionate solipsism is, for all its ridiculousness, no less profound, troubling, or destructive than the obsessed affections of Racine’s Phaedra and Hippolytus. Also, Orgon’s redemption, by fiat of the king, seems no less arbitrary than the vengeful caprice of Venus or Neptune in Racine’s tragedy.

Since the characters cannot change in Moliere’s comedy, then change must happen to them. Moliere’s most brilliant device here arises in the person of the king’s officer, who appears to apprehend Tartuffe and to restore Orgon and his family to their property: property is what establishes the position, the place, the social and individual identity of these characters. Although Moliere’s might be regarded as an elegant (though somewhat clumsy) compliment to the king—and, perhaps, as a sly jab at the clerical critics who attacked Tartuffe—this device plays a subtle role in dramatizing the nature of royal authority. For in Tartuffe, the king has the power to assign every person to his/ her proper place, to see into our inmost hearts, to structure the moral and social order of the world as the reflection of his own will and judgment: “L’etat, c’est moi.” In this sense, even though Tartuffe unleashes the uncontrollable power of self-delusion, and the power and destructive fantasies of absolute authority. It concludes by asserting the legitimacy of that absolute power. Moliere’s deus ex machina testifies both to the power and the arbitrariness of the king’s authority.

IP’s intention to presentTartuffe in 2018 is primarily to include a great period classic play during its 40th Season celebration. It is, of course, joining Thornton Wilder’s Our Town (September-October) and Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie (May 2018). Come celebrate with us!